The Regie [tobacco] Company strike

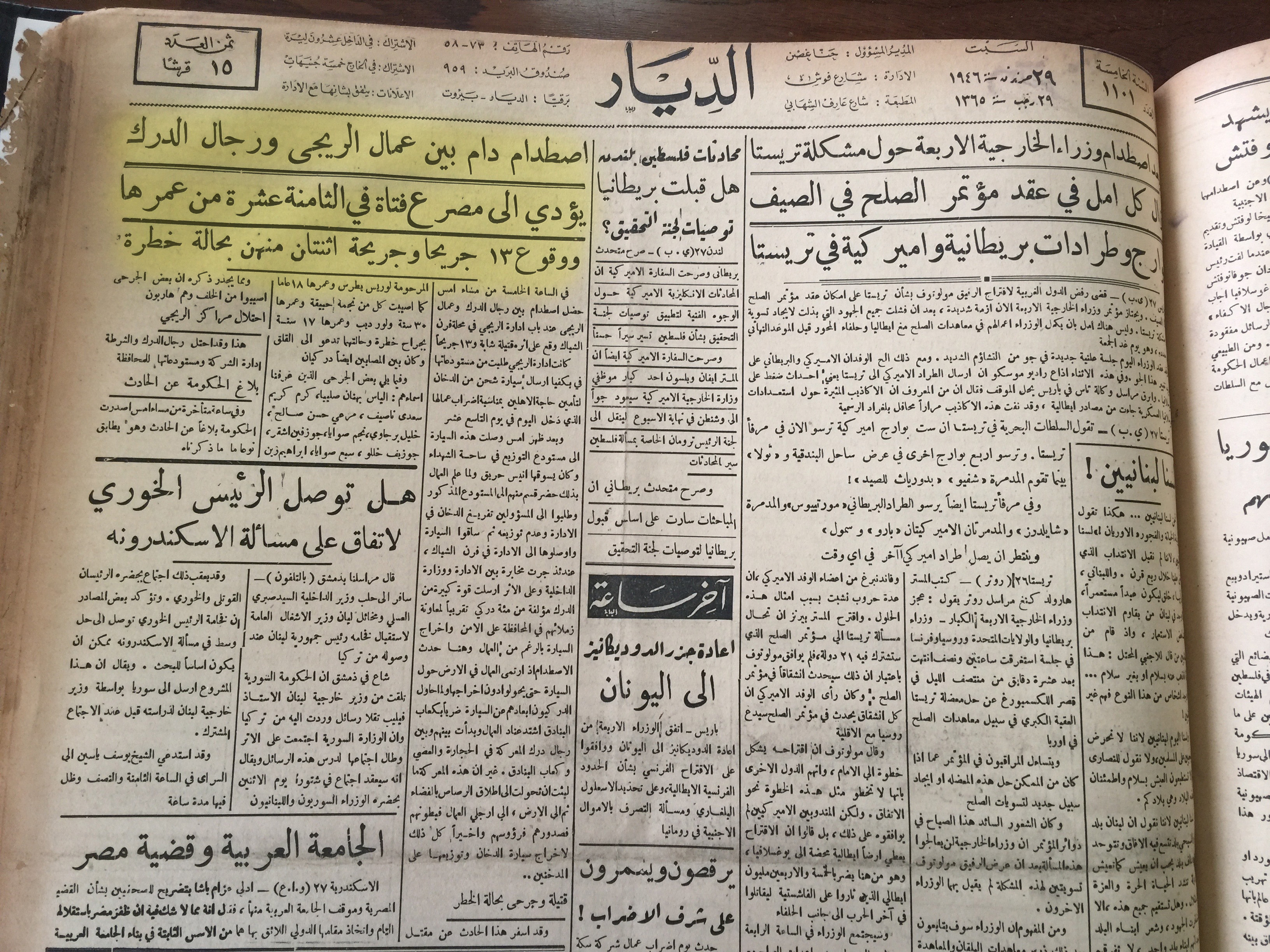

In June 1946, men and women working at the Regie threatened to hold a general strike unless the administration agreed to their demands, which included wage increases and receiving long-term contracts. When the administration did not respond to their demands, women workers called for a strike. The strike started officially on 11 June 1946, with several influential organisers being transferred from the company’s branch in Beirut to the Tripoli branch in order to enfeeble the movement. Nevertheless, the strike withheld these pressures for a month, until the company’s administration invited workers to end their strike in return for studying their demands. When the workers failed to see any signs indicating that the administration would listen to their demands, they occupied the company and the storages. Men and women workers organised themselves into two committees that managed the strike.

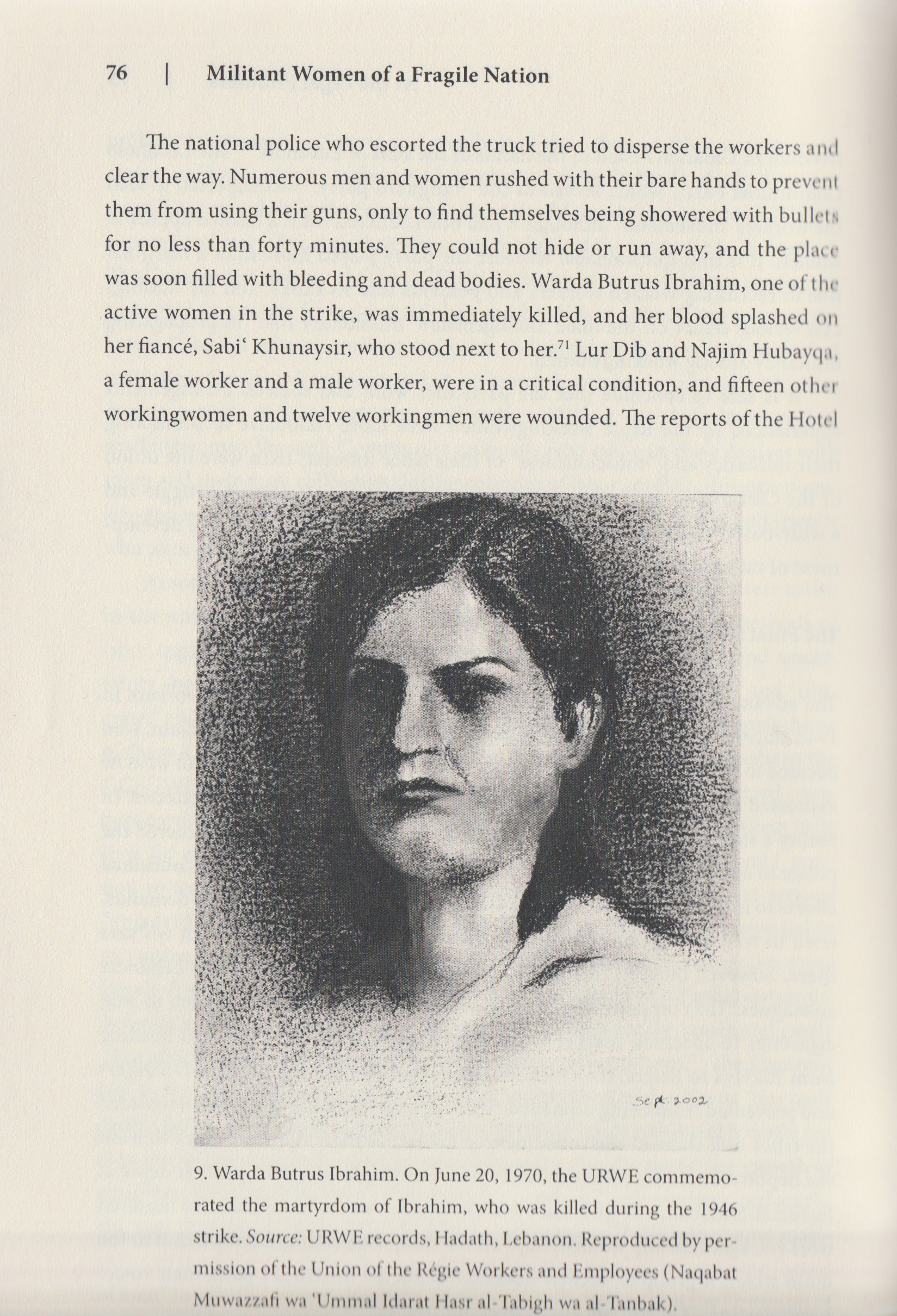

What was unprecedented about these committees was the fact that the first one to be formed was headed by a woman, Asthma Malkun 1. Workers blockaded the company’s distribution trucks from transferring cigarettes to the market, resulting in bloody confrontations between the workers and the police forces that got deployed in the strike’s premises in Mar Mikhael and Furn el-Chebbak neighbourhoods. The first victim to fall was Warda Butrus Ibrahim, who was shot by the police on 27 June 1946. Though the deaths and casualties caused by the Regie strikes and culminated in the passing of the Lebanese Labour Law on 23 September 1946, it is worth noting that the Regie strikes did not transpire alone. Beginning in 1925, there were significant efforts targeted towards building unions and holding strikes across the soap-making industry, publishing houses, and the shoemaking industry, among others. 2

Regarding the absence of records for working women’s participation in mobilisation for their rights, Farah Kobeissi, a feminist political activist, said:

“There is no documentation of the women’s movements with regards to their demands for social justice. There is clear marginalisation and silence about women because the majority of their movements existed outside of organised structures or syndicates. We only know of two incidents where the names of women were mentioned: Warda Butrus of the Regie factory and Fatimah al-Khawajeh of al-Ghandour factory. What they both had in common was one thing: the fact that they were martyrs – as though women could not be known until they die. Not much was known about Fatimah’s life; it’s only recently that people started talking about her and tried to trace her life.

Whoever was handling the archival work back then – be it in the media or from the syndicates – did not focus on the role of women because of the assumption that syndicate members are men, and that the ideal worker is a man who supports his family, not a woman who supports hers.” 3