Foreign women could obtain Lebanese citizenship

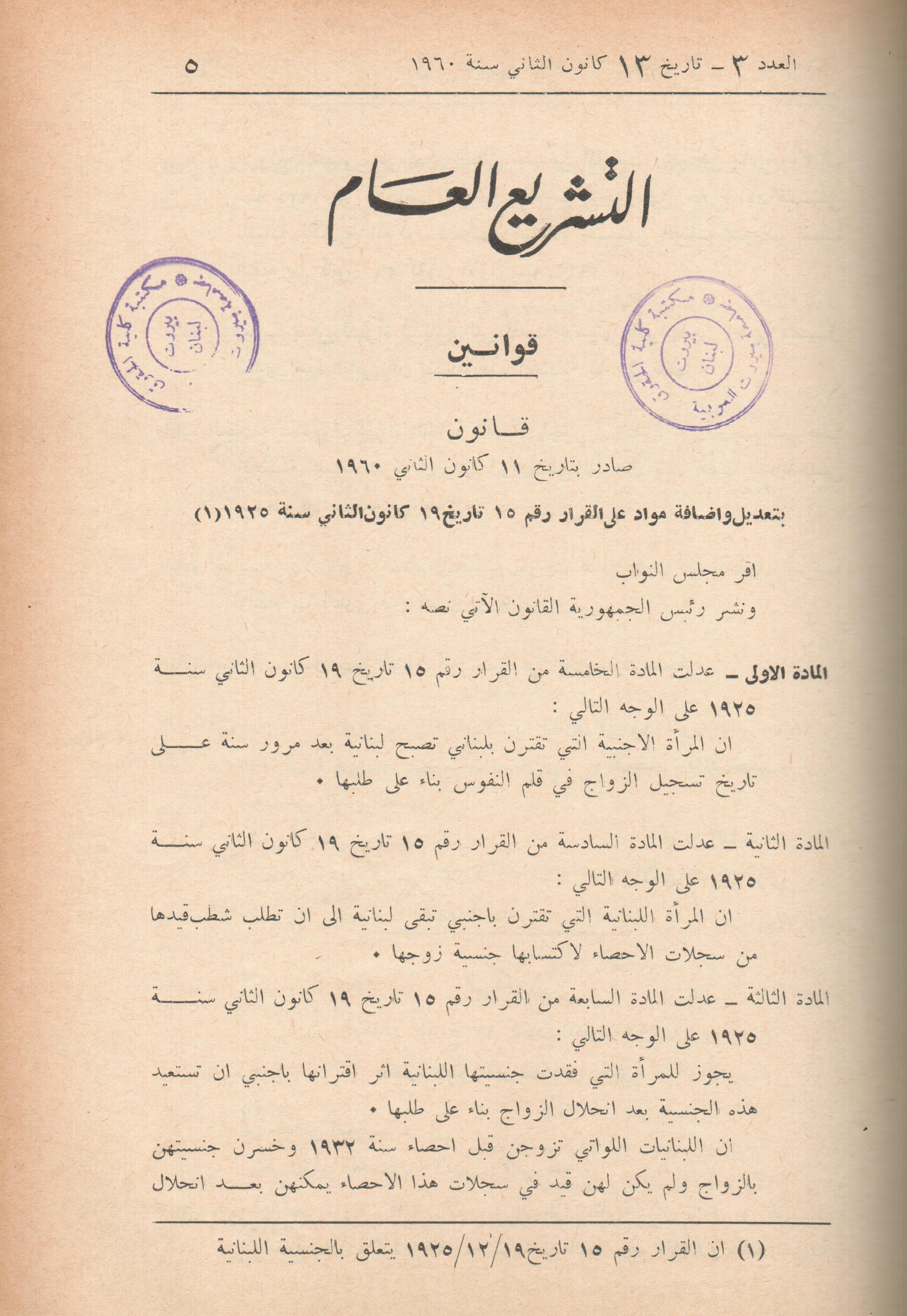

Article 1 of Law no. 15 issued in 1925 stipulated that the Lebanese nationality is to be passed through a) patrilineal/paternal line (having a Lebanese father); b) the right of the soil (being born on Lebanese land) without holding another nationality at birth; or c) being born on Lebanese land to unknown parents or to parents with an unknown nationality. On 11 January 1960, some amendments were passed to improve the status of women acquiring the Lebanese citizenship. Article 5 of Decree no. 15 was amended to allow foreign women married to Lebanese spouses to become Lebanese citizens, and to pass over the Lebanese nationality to children from previous marriages. Ironically, however, these amendments did not apply to Lebanese women (Article 4 of Decree no. 15 issued in 1925).

Until today, Lebanese women are not able to pass on their nationality to their spouses or children; in other words, nationality cannot be acquired through maternal line 1. There are two instances in which a Lebanese mother can grant the Lebanese citizenship to her children: the first is if her children are “illegal,” minors, and she recognises them as her own 2; the second is if the mother is unmarried, and her children have remained without a nationality for a year after their birth. This discrepancy between men and women concerning nationality law is symptomatic of the confounding effect of patriarchy and the confessional system on discrimination against women. A UNDP study conducted in 2008 estimated the number of men, women, and children who are affected by the ongoing nationality codes to be 77,400 3. Nationality and citizenship rights remain a contentious issue for the government, and are continuously evaded and relegated to the threat of naturalisation and resettlement of Palestinian and Syrian refugees. Nevertheless, the discriminatory origins of the law dating back to 1925 are unrelated to the Palestinian and Syrian refugee crises. 4